Bright idea: Companies often neglect innovation that originates outside the organisation

We tend to think of innovation as something an organisation does internally using its resources, capabilities, and processes in a highly structured manner.

Most large organizations build dedicated departments for innovation, such as Amazon’s Lab126 or Alphabet’s moonshot factory X. Leading consulting and professional service firms invest in thought leadership units, such as BCG’s Henderson Institute or the McKinsey Global Institute.

This planned approach to innovation is how most established organisations try to expand the envelope of their businesses.

Despite its dominance, however, it is not the only path. Focusing efforts on this structured, internal approach downplays other crucial routes to innovation.

Involving outsiders in innovation

Some organisations augment the classical internal approach by inviting ideas and new thinking from outside. Examples include Shell’s Gamechanger, 3M’s lead user innovation, or Lego Ideas.

These are initiatives designed to gather ideas developed externally, or collaboratively within organisational boundaries, to develop them further using the expertise and resources of the organisation.

For more targeted challenges, organisations may crowdsource solutions using platforms like Eli Lilly’s Innocentive. Such open innovation or open strategy initiatives can cast a wide net and bring in fresh thinking from groups of stakeholders who are not normally consulted deeply on innovation matters.

Organisations can do a lot to foster creativity, encouraging and allowing for access to diverse building blocks of innovation by opening up to external inputs in this way.

Indeed, corporate “vitality” (the potential for future growth) is predicted by, among other things, an externally oriented culture.

And the science of imagination suggests that it is triggered by surprise and pattern breaking, which will be more frequently encountered by extroverted organisations than more conservative introverted ones.

Four paths to innovation

As an alternative to a traditional, highly structured approach to innovation, we also need to consider approaches that are more emergent, social, serendipitous, and interactive.

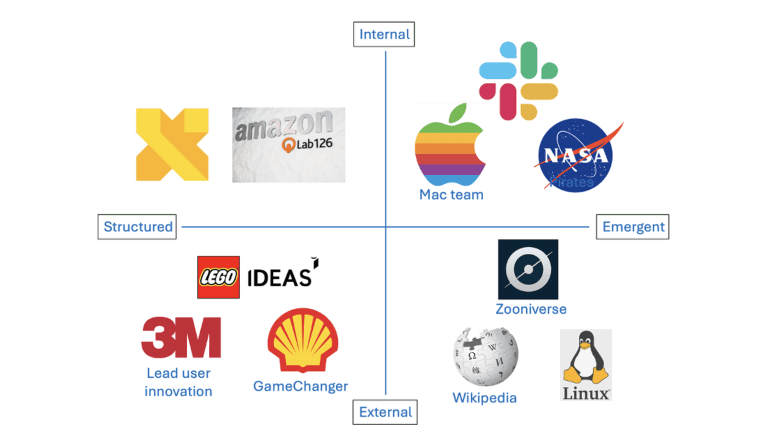

The figure below shows four paths to innovation, based on degree of structure versus emergence, and the source of ideas being internal or external. These form four quadrants that are very different but complementary paths to innovation.

Looking at the internal and emergent quadrant on the top right, unplanned initiatives can grow to become field-shaping innovations.

Slack, the viral collaboration software, was created in 2009 by engineers in a small start-up called Tiny Speck, which was at the time developing a virtual game called Glitch that ultimately failed.

Slack, or “Searchable Log of All Conversation and Knowledge,” was created for the engineers’ own use, to solve the problem of collaborating with colleagues across countries and time zones on a variety of interconnected tasks.

When it was clear that Glitch would not work, it was killed in 2012. However, the company realised they had created something powerful in Slack and pivoted to launch it as enterprise collaboration software in 2013 as the company’s main product, rebranding the company as Slack Technologies.

How mavericks can drive innovation

Innovation initiatives in this quadrant can also arise from individuals who see weak signals on where the market is headed that may be missed by formal processes, or who are driven by imaginative visions of the possible.

These people are often seen as being unrealistic, or as rebels and troublemakers. But such mavericks are a precious source of diverse thinking, intellectual courage, and pattern breaking, which is crucial to the long-term prosperity of organisations.

The NASA pirates, who invested years to build a new mission control for the agency without being asked to do so, simply because they believed it was necessary, are a prime example.

So are the engineers who developed Toshiba’s word processor and laptop computer below the company’s radar. Meanwhile, the first MacBook was developed by a few committed Apple employees in a makeshift space over a gas station, away from the company’s red tape.

Such “underground” innovations can emerge because committed individuals see a better way to address a work challenge, change how an organization does things, or are passionate about realising new possibilities.

The neglected quadrant of innovation

The most underappreciated and neglected quadrant of innovation, however, is on the bottom right.

This is where emergent innovation occurs outside the organisation. The building of Wikipedia and Linux operating systems, for example, indicate that exceptional things can be created if individuals see them as worthwhile and see a bigger purpose in making a contribution.

Zooniverse, the citizen science platform that involves three million volunteers, has made impressive contributions to knowledge in terms of publications and scientific discoveries such as new celestial bodies and neural circuits.

The development of the ubiquitous “like” button is a prime example of external, emergent innovation. It emerged not from a formal project in the innovation department of a large company, but rather from the collective efforts of numerous small enterprises.

Early social platforms were already exploring micro-interactions two decades ago. Vimeo introduced a “like” button in 2005, inspired by the “Digg” button of Digg.com. FriendFeed then introduced a “like” button in 2007, before being acquired by Facebook in 2009.

At Facebook, the “like” button was eventually championed by small informal teams at a time when top leadership was firmly against the introduction of a “like” button.

Once introduced by Facebook however, the button quickly became a transformative feature not only for the company but also for social media and advertising industries and eventually the internet as a whole.

How to harness imaginative ideas

What does the neglected quadrant mean for organisations? For incremental innovations that are somewhat plannable and well within the scope of a company’s knowledge and capabilities, other quadrants may suffice.

But to tap into the most imaginative and transformative possibilities, companies need to harness the power of collective intelligence and serendipity.

Beyond investing in their own R&D, companies must be open to boundary-spanning innovations that may draw from customer behaviours, business ecosystems, or competitor/ collaborator experiments. At the same time, structure must not supress the emergence of the unexpected.

Serendipity is not entirely random, however.

The chances for serendipitous discoveries can be maximised by creating the right conditions, through facilitating access to new ideas, resources, and interactions, from wherever they may arise.

This article was originally published by the BCG Henderson Institute.

Further reading:

Overcome three barriers to successful strategy

Multidexterity: How Lego and Netflix achieved digital success

Three steps to involve front line staff in open strategy

How to overcome fear of failure and foster innovation

Loizos Heracleous is Professor of Strategy and teaches Strategy and Practice on the Full-Time MBA, Executive MBA, and Global Online MBA.

Martin Reeves is Chair of the BCG Henderson Institute, coauthor of The Imagination Machine and Your Strategy Needs a Strategy, and a regular contributor to Harvard Business Review.

Master strategic agility, resilience, and frameworks that support innovation on the four day programme The Strategic Mindset of Leadership at at WBS London at The Shard.

Discover more about Strategy and Organisational Change. Receive our Core Insights newsletter via email or LinkedIn.

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube Instagram

Instagram Tiktok

Tiktok