Growing remit: Some believe the Bank of England should target growth and employment like the US Federal Reserve

In recent years there have been numerous calls to review the Bank of England’s mandate.

Some have suggested that the Bank of England (BoE) should have a dual function like the Federal Reserve System in the US.

This would require the BoE to target economic growth and employment, alongside it’s existing responsibility to use monetary policy to target the rate of consumer price inflation at two per cent.

So why doesn’t the BoE have a dual mandate like the Fed, and what would be the likely impact of such a change?

The rise of the single mandate

After the Second World War, the Bretton Woods System meant countries fixing their exchange rates to the US dollar (USD) and had to adjust their money supply and interest rates accordingly. Meanwhile, the US pegged the value of the dollar to gold at $35 per troy ounce.

This ‘gold exchange standard’ regime lasted until 1971, when it unravelled due to inflationary pressure in the US, driven partly by the Vietnam War, and because other countries came under pressure to revalue or float their currencies.

Inflation rose globally following the oil crisis of 1973 and proved difficult to bring back under control. There was widespread economic chaos, and recession in many countries.

By the late 1980s a new academic consensus had emerged – that central banks should be given independent responsibility to set interest rates to bring inflation under control, while it should be the Government’s job to focus on the real economy and labour markets.

The era of inflation targets began in New Zealand in 1990 and its success encouraged others to follow suit. The UK had an interim regime, with the Treasury setting interest rates from 1992, until the newly elected Labour Government set up the current framework in 1997 with an independent Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at the BoE responsible for setting interest rates.

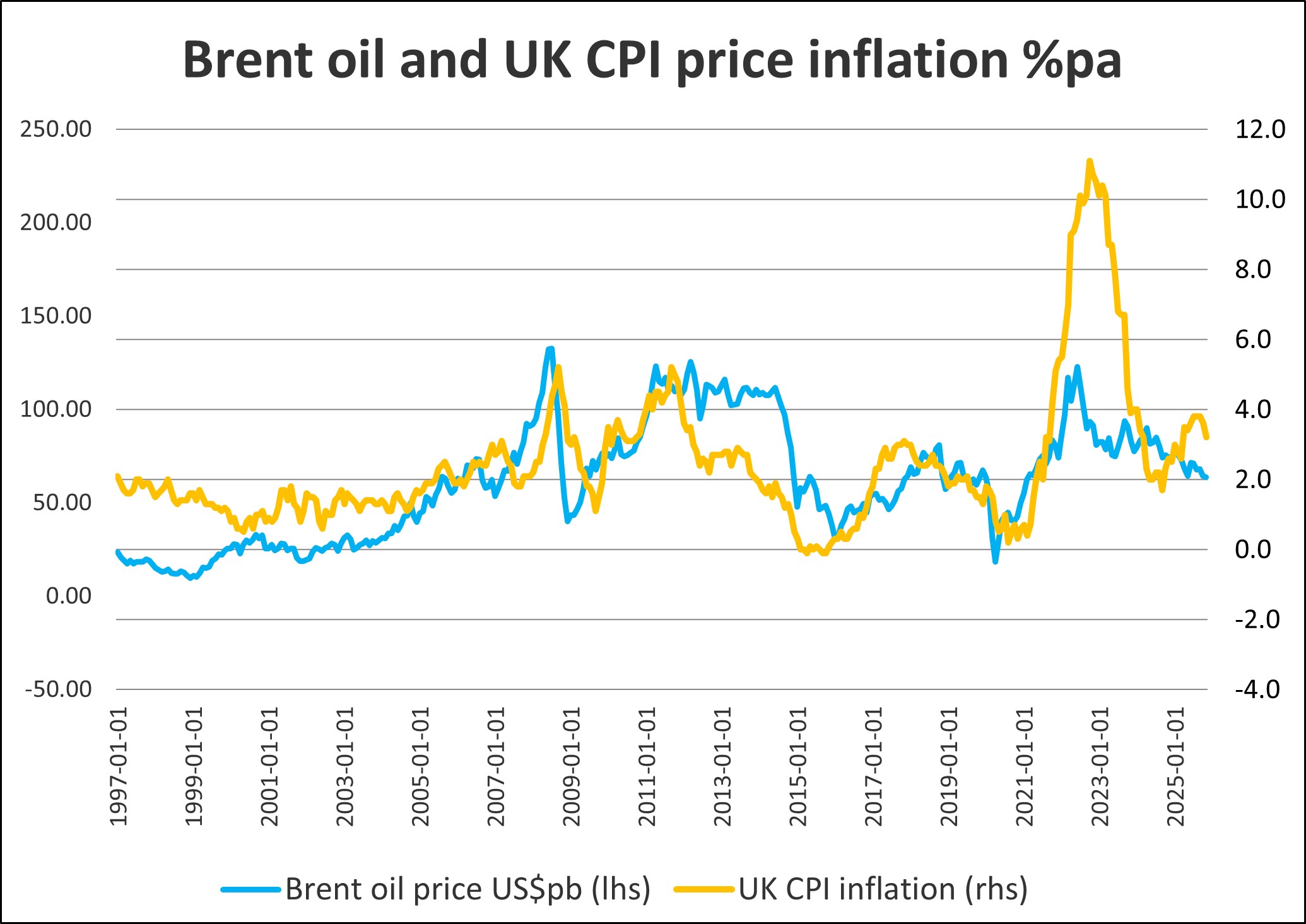

Inflation Targeting (IT) has proved extraordinarily successful in keeping inflation under control. From the creation of the MPC until the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK had an average rate of inflation in the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) of almost exactly two per cent.

The Federal Reserve's dual mandate policy

The Fed’s famous ‘dual mandate’ was formalised in law in 1977, in the light of the economic travails of the time and preceded the theoretical and practical consideration of IT regimes.

It’s mandate from congress is: “… promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.”

In an interview with Marty Feldstein, Professor of Economics at Harvard University, published in 2013, former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker said: “I’m against it.”

“It kind of gives the impression that the Federal Reserve has the keys to the kingdom – that they can achieve price stability and low unemployment at the same time, and it doesn’t matter what the budget is, and all the structural problems in the economy … Monetary Policy will solve all problems.

“I think that’s a bad message to give, because I don’t think it’s right. I don’t think it’s possible anyway.

“The best contribution of the Federal Reserve can be to maintain price stability.”

The economics of inflation targeting

IT stands on a number of assertions which arise from economic theory and which seem to be approximately true, based on experience:

- The sustainable rate of growth is not much dependent on monetary factors, other than that it could be adversely affected if inflation is high and/or volatile.

- Real output over time is determined mostly by real productivity growth and the size of the labour force.

- Productivity growth depends on capital investment and labour force investment – for example through education and health.

- The level of unemployment depends on frictions in the labour market that prevent it clearing.

These real outcomes depend on the Government’s fiscal and legislative policies, but hardly at all on monetary policy.

Sometimes the correlation between inflation and output is positive, sometimes it is negative.

If there is a boost to aggregate demand – from a cut in interest rates or taxes, or an increase in Government expenditure – then output will initially rise and unemployment will fall.

But demand cannot continue to out-strip supply for long. Imbalances build up, as well as prices rising, and eventually a collapse in demand will deliver a ‘bust’ to follow the ‘boom’. Inflation will rise and fall roughly in line with output growth, but with a lag of one to two years.

The longer a correction takes, the bigger the consequent bust.

Why monetary policy is set independently

Governments in a democracy often want to stimulate the economy through tax cuts or interest rate cuts, because the short-term benefits to growth can accrue before an election with the offsetting ‘bust’ occurring after.

If this behaviour is repeated over time, it can lead to rising expectations of inflation that drive up average inflation outcomes with no net gain in output.

Everyone knows this will happen and that the overall outcome for the economy will, if anything, be worse. But there is always an incentive for politicians to act this way.

Currently, we see the US President putting explicit pressure on the Fed to cut short-term interest rates. This will most likely lead to rising expectations of US inflation and downwards pressure on the US dollar, whilst adding a premium to longer-term interest rates and thus Government borrowing costs.

If the President really wants lower short-term interest rates as soon as possible, he should be supporting the Fed in its anti-inflationary stance, not openly criticising it.

Myopic behaviour from politicians is not new and led economists to recommend that an independent authority set monetary policy, with a credible commitment to controlling inflation.

The job of the independent monetary authority is not to maximise growth at any one point in time. It is to keep aggregate nominal demand in line with aggregate supply as far as possible, so inflation stays low and stable, and real growth will then reach its sustainable maximum over the medium run.

Even during the financial crisis of 2007-09, inflation was driven more by oil prices than by the demand impacts of the financial crisis. In 2015-16, low inflation globally was driven by a sustained fall in the oil price.

The COVID-19 pandemic was not particularly inflationary nor disinflationary in itself, as it restricted both demand and supply. The subsequent rise in global inflation was a delayed reaction to expansionist fiscal policies, supported by loose monetary policy, introduced to limit the downside output effects of the pandemic.

That demand stimulus had its most pronounced effects as economies reopened, including causing a rise in global oil prices.

The war in Ukraine then added to the inflationary surge with an additional energy price spike, including an unprecedented rise in gas prices.

Both the UK and the US have struggled to lower inflation consistently to two per cent ever since.

Supply-side shocks are harder to offset than demand shocks. In the face of rising oil prices, tightening monetary policy would add to the downward pressures on real output. But such shocks are usually temporary and often reversed.

If the authorities can hold their nerve, supply-side driven inflation will often dissipate by itself. Central banks behave accordingly. But success depends on the temporary rise in inflation not becoming embedded and hence persistent.

The importance of credibility in monetary policy

The impact of interest rates on inflation is quite weak and inconsistent.

We know that if interest rates are high enough, they will crush demand and output growth and that will bring inflation down.

We also believe that very low interest rates – accompanied by a big enough monetary expansion – will eventually lead to more inflation.

But everything in-between is a bit imprecise. So why does IT work at all?

IT works well when people believe that the authorities are really committed to it. If people believe the commitment to the target, then price and wage-setting behaviour will largely deliver the result.

All the authorities need to do is move interest rates enough to sustain that belief.

However, if the expected rate of inflation rises significantly, interest rates have to move by much more to offset the impact of higher expectations as well as the root inflationary impulse.

Successful inflation control reinforces itself and so does failure. The recent episode in the UK in which inflation exceeded 10 per cent is itself making it much harder to bring inflation back to two per cent.

Credibility is a central bank’s most potent tool in controlling inflation and everything needs to be done to maximise it when designing and implementing an IT regime.

Transparency boosts credibility, Government criticism undermines it.

Why central banks have secondary objectives

Many central banks have secondary objectives, which require them to support Government policies.

This is even true of the European Central Bank (ECB), the most independent central bank in the world, which according to the Maastricht Treaty: “Without prejudice to the objective of price stability, shall support the general economic policies of the European Community.”

In the UK, secondary objectives are quite common for agencies such as the Financial Conduct Authority and the BoE.

For example, the Bank of England Act (1998) states that the objective of the MPC is:

- to maintain price stability, and

- subject to that, to support the economic policy of Her Majesty’s Government.’

The problem with secondary objectives, is that no-one knows for sure how they should be pursued.

My understanding is that secondary objectives are employed when a Government wants an agency to take something into account, but does not want to give that agency the powers they would need to achieve it.

The MPC cannot deliver full employment because it does not control labour market legislation.

But the Government does not want the MPC to ignore growth and unemployment completely. So, the remit does allow for some degree of MPC action that is supportive of growth, usually witnessed in how quickly the MPC seeks to bring inflation back to target (ie, more slowly after a supply shock).

The political case for a dual mandate

Despite the economic inappropriateness of a dual mandate, could it nonetheless be politically useful? Like Volcker, I would argue against.

One of the problems stemming from the success of IT regimes globally has been that governments have seemed to abandon their own responsibilities for promoting sustainable growth. A dual mandate would surely encourage that tendency.

Positive supply-side policies are often difficult and unpopular. Changes (for example, policies that promote competition) may be resisted by vested interests in large corporations, and equally by some unions which benefit from inefficient resource allocation.

Each warranted supply-side policy will likely upset a particular interest group, and enough of such policies can be fatally detrimental to a party’s political popularity.

This is articulated in the classic Government’s lament, often attributed to Jean-Claude Juncker, former Prime Minister of Luxembourg and former President of the European Commission: “We all know what to do, but we don’t know how to get re-elected once we have done it.”

Undue expectations of what central banks can achieve, or anything else which undermines the credibility of a monetary policy regime, risks de-anchoring inflation expectations, and raise the cost of keeping inflation under control.

If financial markets believe that a dual mandate will encourage loose monetary policy that will add a risk premium both to Government debt and the exchange rate.

The strength of an IT regime lies in its integrity, its independence and above all in its primary commitment to inflation control.

Further reading:

How big should the central bank balance sheet be?

Financial regulation: Making banking an increasingly risky business?

Is the Monetary Policy Committee affected by groupthink?

Why would central banks want to issue digital currencies?

Paul Fisher is an Honorary Professor at Warwick Business School and a former member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee. He teaches on the Global Central Banking and Financial Regulation qualifications.

Discover more about Central Banking and Finance. Receive our Core Insights newsletter via email or LinkedIn.

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube Instagram

Instagram Tiktok

Tiktok