Parliament now has two tracks to resolve Brexit. The Government continues to press its deal with May’s dramatic offer to resign if it’s accepted. And parliament has held the first round of indicative votes to explore another solution.

There is much raw politics here: why a resignation should affect the merits of May’s deal is baffling to outsiders. But are these politics moving parliament towards public opinion or away from it?

The difficulties of May’s deal in parliament reflect its unpopularity in the country – its 12 per cent support in ComRes’ poll last week putting it on a par with the poll tax.

However, two of the indicative votes last night came far closer to a majority than the Government deal has thus far. They both constrain any deal. Closest to being carried was the proposal that any deal should include a customs union, failing by only eight votes. This is consistent with the public’s preference for a softer deal rather than a harder one.

The other near-miss - attracting the most votes, at 268, though with 295 against - was the proposal that any deal be subject to a confirmatory public vote. This would be consistent with some significant public shifts over the last year.

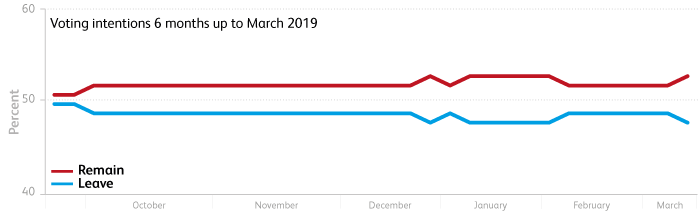

In the 12 months to March 2019, though, a lead for remain has developed that, while modest, is stable and statistically significant. By contrast, leading up to the June 2016 vote the polls swung widely, indicating a voting population still uncertain of their views.

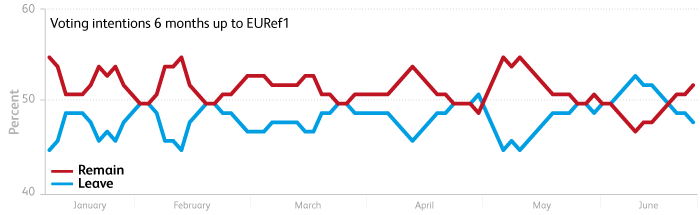

The charts below plot the National Centre for Social Research’s “poll of polls” on referendum voting intention over a six-month period in each case.

The top chart shows the six months leading up to the 2016 referendum. The bottom chart shows the six-month period up to March 2019. A glance at these graphs shows a clear difference in the changeability of voters’ views.

In just two months before the 2016 vote, opinion veered between a Remain lead of 10 per cent and a Leave lead of six per cent. Since October 2018, by contrast, the Remain lead has been rock-steady at six to eight per cent.

But do these polls reflect how people would actually vote? After all, humans exhibit many attitude-behaviour gaps – the bane of market researchers.

We developed a statistical approach to this question in a recent academic paper analysing data from the UK’s 2010 General Election. We tracked a panel of floating voters over four weeks, and compared how they said they would vote with how they actually did. We found we could best estimate the actual vote by considering voter preferences over time, weighing the most recent preferences most heavily.

It turns out you can’t just look at the latest polls: someone who flipped yesterday may flip back tomorrow. Adapting this to the last four weeks of polling data suggests that a second referendum tomorrow would yield a Remain win of 53.6 per cent to 46.4 per cent. (The same approach applied to the 2016 polls yields a narrow Leave win.)

The UK is still starkly divided, but it is no longer a statistical dead heat.

Substantial shifts on the economy and immigration

What’s changed? To start with, people are clearer on what they think about the EU. When surveying customers, good marketers consider not just attitude valence but also attitude strength - how strongly people hold their view. And if you ask people to vote, as happened in 2016, that itself is an intervention that forces people to make up their mind to an extent. Greater attitude strength now accounts for the far stabler polling pattern.

As for the increase in Remain preference, demographics are of course a factor: every year, around 455,000 remain-dominated young people reach voting age, while the 480,000 who die are skewed towards leave.

But how about all the other voters getting older? Some indeed have switched their allegiance: only 88 per cent of Remainers would vote the same again. But even more Leave voters would switch, only 82 per cent saying they would repeat their vote.

Two reasons are likely. Firstly, many of those Leave voters now think very differently about the likely economic impact of Brexit. In May 2018, 42 per cent of them thought that leaving the EU would make the economy better, and only 16 per cent worse. By January 2019, that lead had evaporated (26 per cent ‘better’ and 27 per cent ‘worse’), according to Opinium polls.

Secondly, UK attitudes towards immigration have shown a dramatic reversal in the last few years. In 2011, 64 per cent of people thought that immigration had had a generally negative effect on the UK. By 2019, according to Ipsos MORI, that had reduced to 26 per cent. The inflection point where those thinking immigration was positive began to outnumber those regarding it as negative was in 2016, shortly after the Brexit vote.

After three years of obstinately inconclusive data, then, we can now say that those who would prefer to remain in the EU clearly outnumber those who wish to leave. That might help explain the difficulties in parliament with signing off a Brexit deal of any sort: 67 per cent of MPs’ constituencies now have a Remain majority, according to Populus.

This does not, of course, guarantee that any second referendum in a few months would follow the current polls. To start with, one side might run a better campaign than the other – Leave being widely acknowledged to have run the better campaign in 2016.

Also, to vote one has to turn up – quite different from answering the phone to a pollster. Estimating turnout is currently more of an art than a science: polling companies put far more effort into establishing your preference than in estimating whether you will actually vote.

Would a second referendum end the Brexit debate?

In our General Election study, we found that turnout depends not just on your declared likelihood of voting but also on whether you voted last time (a habit effect), as well as whether you care about highly-charged topics such as climate change and terrorism.

We don’t have enough data from the pollsters to repeat that for referendums.

A third variable in any referendum is the exact question. Ask voters to compare staying in the EU with a specific leave option, such as Theresa May’s deal, and you get higher numbers preferring Remain. And finally, of course, there is the possibility of events prior to a vote swinging opinion.

Arguments about the legitimacy of another vote are, of course, another story. Some will argue that any shift in opinion is irrelevant and that the 2016 poll decision is irreversible. Others say the essence of democracy is periodically checking in with the people.

Nevertheless, as things stand, there has been a significant consolidation of support for staying in the EU. On Saturday, an estimated one million people marched in London to demand a second referendum - a number matched this century only by 2003’s protest against the Iraq war.

The petition calling for the UK to revoke Article 50 and stay in the EU is today approaching six million signatures.

Clearly, Leave is not the only side on which feelings are strong. More significantly, though, the 48 per cent has become the 53.6 per cent. This, more than the current petition and Saturday’s march, will provide ammunition for those arguing for the legitimacy and desirability of a second referendum.

Hugh Wilson is Professor of Marketing and is listed in the Chartered Institute of Marketing's 'Guru Gallery' of "50 leading marketing thinkers alive in the world today" alongside Bill Gates. He teaches Service Marketing and Strategic Marketing on the suite of MSc Business courses.

Follow Hugh Wilson on Twitter @hughnwilson.

Emma Macdonald is Professor of Marketing and teaches Marketing on the Executive MBA and the Evening Executive MBA (London).

Follow Emma Macdonald on Twitter @DrEmmaMacdonald.

For more articles like this download Core magazine here.

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube Instagram

Instagram Tiktok

Tiktok