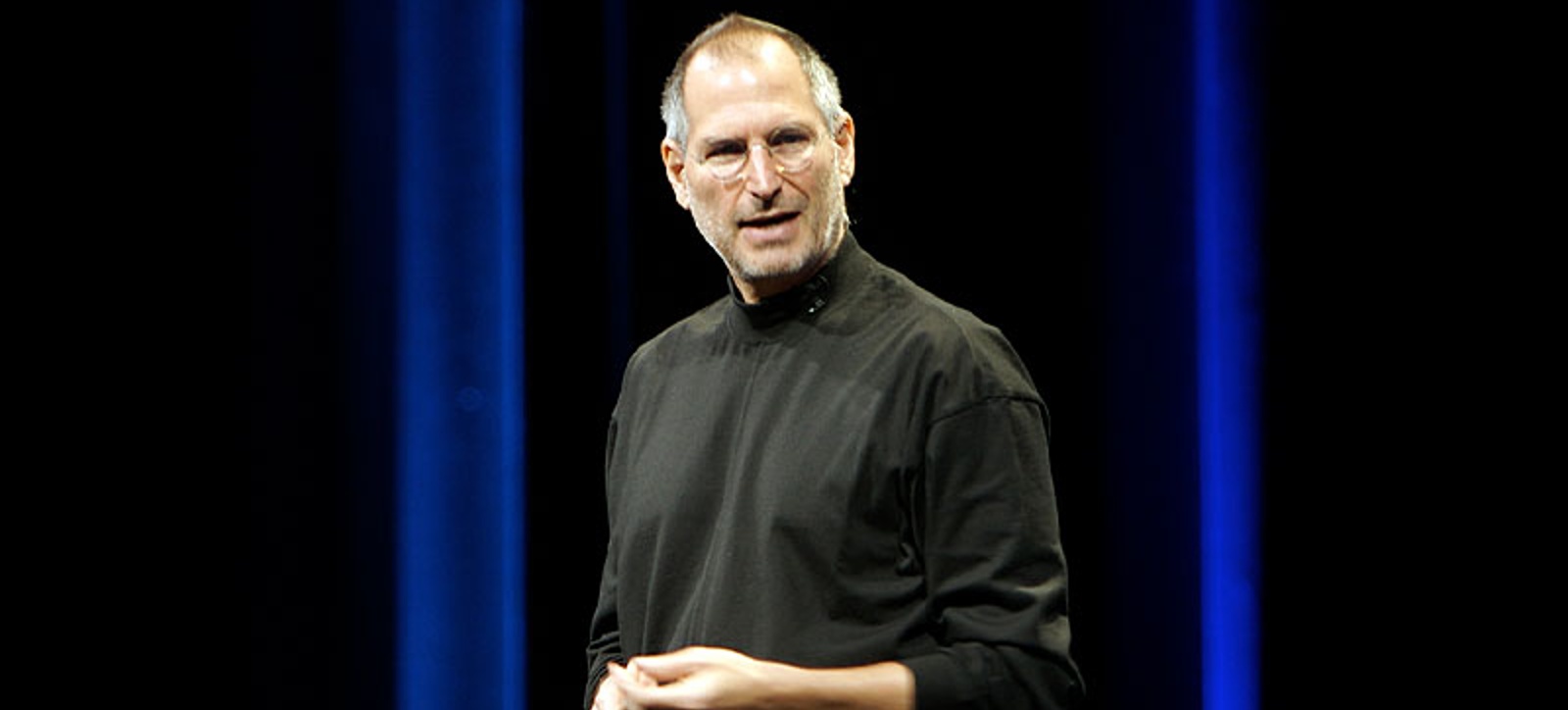

History repeating: Apple co-founder Steve Jobs examined tech giants of the past to learn lessons

When executives face big decisions, they usually try to gather data. However, they know that forecasts are often flawed.

Hence, they rely on their own experience and the experience of others. History is a great way for them to expand their field of vision, drawing from a much wider pool of experiences.

Steve Jobs, for example, referred to Leonardo da Vinci when the Apple co-founder explained why great ideas emerge at the intersection of art and science. And he extensively studied the rise and fall of giants like Xerox to prevent the Silicon Valley tech giant suffering a similar fate. His Amazon counterpart, Jeff Bezos, was inspired by Walmart founder Sam Walton’s obsession with customers and taking a hands-on-approach.

When you recognise patterns in history, they can inspire new ideas, help you to avoid mistakes, and become a powerful way to communicate your ideas.

In the mid-15th century a gunner named Orban offered his services to the Byzantines who ruled Constantinople. The use of cannons was still relatively new and the benefits less obvious. As the Byzantines had high walls that nobody had toppled before, this innovation seemed unnecessary. So they offered Orban a rather meagre salary.

Unimpressed, he decided to seek out Mehmed II of the Ottoman Empire instead. The Sultan was more desperate as the Empire’s previous attempts to take Constantinople had failed. So the gunner got his chance. Sixty-nine regular cannons and dozens of catapults started their bombardment on April 12, 1453 and the city fell just 47 days later.

This story features in Scott Anthony’s captivating new book on 11 disruptive innovations that shaped the modern world. It’s a powerful reminder that incumbents often miss the benefits of disruptive new innovations - in this case gunpowder. The broader lesson from the book is that by looking at history we can find patterns that often seem less obvious if we only consider current developments.

Shell's historical insight shaped its governance

In 1964 oil giant Shell hired consultants McKinsey to develop a new organisational structure. One of the recommendations was to install an American-style CEO. Shell declined, remembering the potential downside of having a powerful leader like Henry Deterding, the architect of the 1907 merger between Royal Dutch and Shell Transport and Trading.

Later in life, Deterding saw Adolf Hitler as the only politician capable of stopping communism. Luckily, he retired in 1936 and moved to Germany, before making any commitments that would have embarrassed the company later on.

The company had learned that in a politically sensitive industry, having a board of executives building consensus is often advantageous. For decades it kept this rather unusual arrangement.

In a study of companies surviving and thriving for more than a hundred years, I found that one of their characteristics was this ability to remember past mistakes.

Obviously, this kind of learning is not restricted to your own mistakes. Follow Jobs’ example and pick a fallen giant in your industry. It’s an effective way to avoid some of the pitfalls awaiting you.

History can also help executives to rally the troops. Current Apple CEO Tim Cook does this frequently when he invokes Jobs’ legacy. This way he can frame new innovations as a continuous journey started by the firm’s legendary co-founder. Many companies with legendary founders - think HP or Walmart - use history in a similar manner.

Another occasion when history comes in handy are in moments of crisis. Politicians do this frequently, knowing that painful reform is hardly popular. In the corporate world, Chrylser CEO Lee Iacocca, drew analogies to the Great Depression during one of the most dramatic turnarounds in US history in the 1980s.

History might seem stuffy and irrelevant but smart executives like Bezos, and Jobs before him, understood that the lessons they could pick up would help them to avoid similar mistakes.

This article is republished from Forbes.

Further reading:

The secret behind Apple's strategy - 'Quantum Strategy'

Why Steve Jobs was such a charismatic leader

Six leadership skills you need to make the most of AI

The four principles of enduring success in business

Christian Stadler is Professor of Strategic Management at Warwick Business School. He teaches Strategic Advantage and Strategy and Practice on the Executive MBA and Global Online MBA.

Discover more about Leadership and Strategy. Receive our Core Insights newsletter via email or LinkedIn.

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube Instagram

Instagram Tiktok

Tiktok