More foreign investment in high-tech sectors means higher wages for workers

Every business strives for success. In the face of intense competition, firms are constantly seeking to gain a competitive advantage in the global market.

And in order to achieve this, they need high performers: managers with advanced skills in decision-making and strategic planning. However, obtaining those skilled managers appears to be a stumbling block on the way to market success. Even leading firms report significant skills shortages in key areas like advanced manufacturing, R&D, finance, supply chain management and many others.

Since the 1990s firms have been increasingly engaged in a global ‘war for talent’, especially in sectors related to science, technology and innovation, with tech firms seeing the highest value added per head and the highest levels of wage growth from the early 2000s onwards. Tech firms, in particular, hunt for the best graduates from top universities as when competition is based on innovation rather than price, skilled labour is a crucial element of market success.

Interestingly, tech firms are becoming more concentrated in their geographies. Multinational firms, as well as new start-ups, are now chasing the same research centres, often attempting to build on existing agglomerations such as Silicon Valley in San Francisco, Medicon Valley in Denmark, or the ‘Golden triangle’ in the UK. Moreover, innovative industries are concentrated in a limited number of locations. For the regions concerned, this results in a higher competition for labour and, consequently, higher wages.

These days, technological clusters are developing at a fast pace. As such, high-tech firms attract large amounts of foreign direct investment (FDI) – one of the factors that boosts their development. Investors purchase local companies directly or locate business activities abroad through subsidiaries.

From 1991 to 2012 foreign investment stock in high-tech industries in developed countries grew 12 per cent faster than the market average and 81 per cent faster than FDI in manufacturing sectors. This continuous expansion subsequently requires more workers and with the required skills in short supply it means that an increasing number of firms are becoming involved in a global war for talent.

But what makes tech so special? Firstly, labour market conditions are specific in technology and research-intensive industries. Already scarce, skilled labour is therefore better paid. Tech workers are also mobile in nature – willing to travel further in the pursuit of higher income – so it comes as no surprise then that the highest-skilled workers are more likely to end up in one of the large technological clusters with a strong inflow of FDI.

For these clusters, what impact does FDI activity have on wages and employment? We set out to explore this by analysing six research-intensive sectors including chemicals, pharmaceuticals, computers, electronics, R&D and other scientific activities in 28 European countries over a nine-year period (2002-2010). Europe makes an ideal research setting as the European Union plus Norway constitutes the second largest single market in the world, with free movement of labour and free trade.

At the same time, substantial differences are present at both national and regional levels, among them the availability of high-skilled workers, innovation capacity and the amount of FDI.

As a general rule, the effect of FDI is usually regarded as positive – thanks to the inflow of cash from abroad, local companies benefit from the transfer of technology and expertise. However, it is not as straightforward as it might seem, because intra-firm technology transfer may also generate a productivity gap between foreign and local firms. And in this case, local firms will struggle to prevent their workers from leaving for a better-paid foreign firm, subsequently having to offer higher wages or reduce their workforce.

Our research shows that an increase in FDI in high-tech sectors was accompanied by an annual five per cent rise in domestic wages, though domestic employment grew by only 1.1 per cent per annum – a glaring example of how foreign activity can actually squeeze skilled labour out of the domestic market. ![]()

![]()

Does it mean that foreign investors are no longer welcome? Of course not. FDI can generate huge positive effects on local economies, not least – as mentioned previously – the transfer of technology and expertise that provides enormous benefits for local companies.

Moreover, if a firm has a strong market position, high profitability and can positively manage the spillover effects of FDI, it can also absorb wage increases at almost no cost. In this case, FDI inflow eventually has a positive impact on profits.

So, what could help maximize the benefits associated with FDI while offsetting their detrimental effects on local firms? Our research shows that the key factors are labour market flexibility – how quickly firms can respond to changes. Plus the capacity to assimilate knowledge or technology that accompanies the foreign investment, either directly through, for example buyer-supplier relationships, or through various 'spillover' mechanisms, such as workers moving between firms and taking the knowledge with them, through agglomeration benefits or through local firms adopting better business practices.

These two factors depend heavily on a number of internal criteria, including the size of the business and its profitability. There is also an important external factor: the host country’s level of development. This plays a crucial role in moderating the ability of local firms to embrace foreign technology.

All of these factors determine whether a ‘crowding out’ or a technology effect dominates – that is, whether domestic firms lose or gain from the presence of FDI.

More developed economies tend to be able to better withstand demand shocks and have higher labour market and wage flexibility. On the contrary, less developed economies tend to be less resistant to the adverse effects of FDI, with lower flexibility and fewer capacities to quickly reallocate resources in response to the required changes. ?

In determining the level of flexibility of a labour market in a given region, it is necessary to consider the role of market institutions. They can help draw a line between more liberal market economies and co-ordinated market economies.

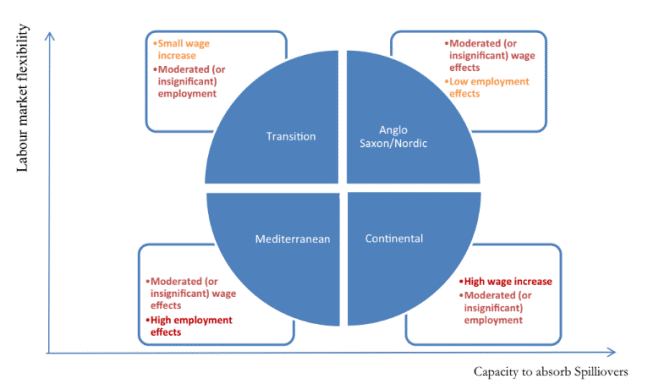

We have distinguished four distinct groups: Nordic/Anglo Saxon, Continental, Mediterranean and Transition economies.

Mediterranean countries have higher levels of labour market protection and segmentation. The Nordic model is characterized by high levels of social protection and welfare provision.

In the Anglo-Saxon model, unions are weak and wages have a bigger dispersion. And in continental countries such as Belgium, Germany and France, there are stronger unions, and relatively higher levels of labour market segmentation. The graph below illustrates how each of these groups of countries differ in their flexibility and potential to absorb the harmful spillover effects of FDI.

In general, liberal market economies have higher levels of labour market flexibility. Anglo Saxon/Nordic countries have both the highest market flexibility and capacity to absorb spillovers, with their firms more likely to benefit from FDI without experiencing negative consequences on domestic wages and employment. On the other side of the scale there are the Mediterranean economies, who are more exposed to negative spillover effects. In those regions, foreign activity is more likely to push wages upwards and crowd out domestic employment.

Understanding FDI effects on labour markets may be interesting for both national and regional policymakers. It can help them understand how to make the most of incoming FDI and at the same time put in place measures to protect local firms from adverse spillover effects.

First and foremost policymakers need to understand what kind of market they are dealing with. If the market is more rigid – as in the cases of Transition or Mediterranean economies – governments should think about how to improve flexibility. This suggests, for example, putting emphasis on education and training as well as supporting small local firms.

National policies that promote domestic R&D investment and innovation strategies are also helpful in turning foreign activity to a country’s own advantage. After all, R&D and innovation enhance local firms’ productivity and capacity to exploit spillovers.

At the same time, higher domestic R&D and innovation are likely to raise the attractiveness of a region for foreign investors. Tax credits, direct subsidies, collaborations between universities and firms all increase the available pool of high-skilled labour and support regional development.

The global war for talent puts upward pressure on the earnings of that talent. And regions with a strong FDI inflow will not be immune to these increasing wage costs.

The ultimate goal of policymakers is not to prevent foreign investors from pouring their money into local economies, but to augment the positive effects of such activities. The potential is in fact huge, and for many economies across the globe is yet to be discovered.

Further reading:

Becker, B., Driffield, N., Lancheros, S. et al. FDI in hot labour markets: The implications of the war for talent. J International Business Policy 3, 107–133 (2020).

Driffield, N., Jones, C., and Kim, J-Y., Temouri, Y. FDI motives and the use of tax havens: Evidence from South Korea. Journal of Business Research, 135, 644-662 (2021).

Nigel Driffield is Professor of International Business and teaches Law and the International Business Environment on the Undergraduate programme.

Follow Nigel Driffield on Twitter @nigel_driffield.

For more articles on Finance and Markets sign up to Core Insights here.

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube Instagram

Instagram Tiktok

Tiktok